INK & GRIT - "This is the Way I Make My Bread" by Frank Gruber

INK & GRIT: Masters of Pulp Fiction

Editor’s Note:

If you missed the early parts of the INK & GRIT: Master of Pulp Fiction series you can catch up below.

START HERE

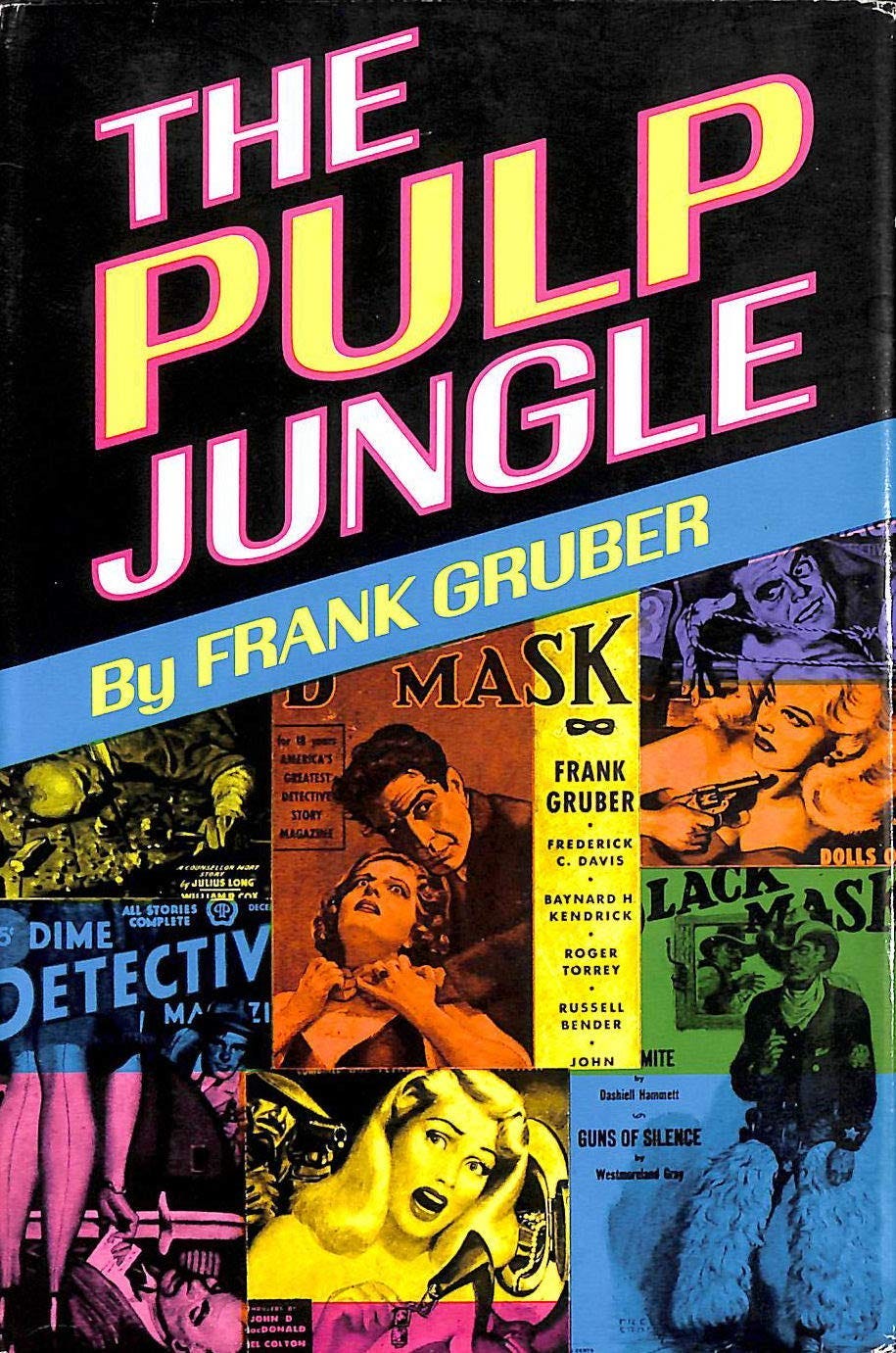

Today we look at the words of Frank Gruber (1904-1969), a pulp fictioneer who penned over fifty novels, dozens of short stories, and hundreds of screenplays for film and television—a testament to his incredible and relentless work ethic.

His memoir, The Pulp Jungle, offers a detailed account of his writing career, starting from his early struggles and culminating in his remarkable achievements. It is a recommended reading for any pulp enthusiasts and those curious about the inner workings of a prolific writer of that time.

This 1941 Writer’s Digest article details a typical day for the pulp writer.

Enjoy.

A LETTER FROM Aron Mathieu this morning. Aron’s always good for a chuckle and this time is no exception. Witness this:

“Frank, my pretty lug, I want an article from you for our October issue, which gives you two days to write this piece, a day to cool it, another day to reread it and throw it away, and then a full day ti write a good one.

More than anything else, I would like our readers to be able to have a personal talk with you, about what you are doing , and how you are doing it. I’d like you to tell them what you think about writing, the little difficulties you encounter, the bigger problems that beset you, the way you solve them; the way you live, how you work, what goes on with you. It should be a living, breathing piece of writing, raw, human, but leave out the women; a little tragic if need be, and end on the inimitable, if somewhat baffling, a genuwyne Gruber note. The length is as she blows.”

So help me, that’s what Aron wrote and if he has nerve enough to print his letter, then I’ve got nerve enough to publish the answer.

“I’ll give you a week with Gruber and at least 75 percent of it will be the truth. A fiction writer should be allowed 25 percent latitude.

Monday:

I get up around eight o’clock on Mondays, because that’s the day I always go downtown. I dress hurriedly and drive down to the postoffice for the mail. There are three mystery novels to review for the Chicago Daily News, for which I do a weekly column of mystery reviews. There’s a copy of Publisher’s Weekly, the book trade journal to which I subscribe; three bills, and a post card from a woman in New Jersey, who read one of my stories. There’s a letter from Steve Fisher, who is knocking them dead in Hollywood; another from George Shaftel, telling of signing his first book contract.

I drive to the station to catch the 9:06 train to New York and bump into Captain Shaw, former editor of Black Mask. Haven’t seen him in some time. Have a grand session in the smoker wit hthe captain, with him talking about Dashiell Hammett, Raoul Whitefield, Fred Nebel and Carroll John Daly. He tells me Ray Holland is resigning from Field & Stream, after 20 years, to write.

At the Grand Central in New York, Shaw goes one way and I go another. I hurry down to the offices of the New York World-Telegram, where I have a date to be interviewed by Allen Keller, staff writer. A half hour is spent there and I get my picture snapped. The prints are ready before I leave and I am chagrined to discover that I am becoming a fat guy.

From the World-Telegram I ride uptown to the offices of Short Stories in Radio City, as nice an editorial office as you will find in New York. I have a business discussion with Dorothy McIlwraith and tell her I am half finished with the novel I am doing for her I am half finished with the novel I am doing for her and will bring it the following Monday. She knows very well, from past experience, that I won’t have the story in for two weeks, but doesn’t call me a liar.

Peter Kuhlhoff comes in. Pete is one of the best artists in the business and a shark on guns. Also he is the biggest guy you ever saw in your life, standing six feet eight inches. We chin about guns and Pete tells me that Navy Colts were rifled before the Civil War, which I hadn’t known before.

After Pete leaves I step in to see Bill Delaney, publisher of Short Stories, and we wind up by going out to lunch at one of the Radio City restaurants. We engage in a series sociological discussion. Bill tells me how he cleaned out his entire Marine company in France playing blackjack and I retaliate by relating the time I made 17 passes with the dice when I was in the army.

After lunch, I go down to Farrar & Rinehart’s office and tell John Farrar about an ideal I’ve got for my next novel. He tells me about it’s swell, knowing damn well that the story I’ll finally bring in will be entirely different. I run into Phil Hodge, the sales manager, and tell him a couple of gags I hope to use in a story. He doesn’t laugh at them, which discourages me. In the corridor I waylay Stanley Rinehart and spring the same gags on him. He doesn’t laugh either, so in desperation I go and trap Mark Saxton, advertising manager, who laughs.

When I leave Farrar & Rinehart I go down to Street & Smith’s office and receive the disconcerting information that The National Magazine is no more. I had sold them several stories. While searching for John Nanovic’s office I run into Bill DeGrouchy, who tells me his wife like The Hungry Dog, and I ask him why he doesn’t read it himself. I get lost among the rolls of paper, stockrooms, etc. But I finally locate John Nanovic’s lair. Just outside the door I encounter “Mo” Jones and exchange insults with him.

John’s office has been moved again. (Editor’s offices move continuously at Street & Smith’s, the idea perhaps being that if an author can find an editor’s office he must be a smart guy and therefore worthy of writing for the magazine.)

John has letters on his desk from Ted Tinsley, Lester Dent and Walter Gibson. He tells me what each is doing and I tell him what Steve Fish wrote me. I pull out two snapshots of our baby and John retaliates with a fistful of his own. His is twice as old as mine, so he always has the edge.

I leave Street & Smith and take a taxi to Grand Central. I find I have 20 minutes until my train leaves, so stop in at the Doubleday Doran book store, where they do very well with my books. I am merely trying to kill time until train time, but wind up buying a copy of Whistle Stop and a book on Death Valley.

I rush to the train, buying a copy of the World-Telegram, the Journal-American and Life, timed to last me to Scarsdale, 38 minutes from Grand Central.

I stop at the postoffice again on my way home and find a letter from Swanie (H. N. Swanson, my Hollywood agent). Home, I fool around with the baby, who has just started to walk at the age of 11 months, have dinner and take the family for a drive. We return in time to get all the war news on radio. The baby goes to bed and I start reading Whistle Stop. I read until nine o’clock, when the wife asks me if I’m going to do any work or not.

"Tell us a story, Daddy."

So it’s come at last.

The noiseless typewriter is on the bridge table in the living room and the regular in the office on the sun porch. I decided that I want to work on the sun porch, but want the Noiseless. In exchanging them I knock some magazines and hooks to the floor and dis- cover my account book. I decide to figure up my income so far this year and estimate my probable income for the year. This is interesting and I kill a pleasant hour.

I’m faced with the typewriter and a nice clean sheet of paper. I look at the paper and put my fingers on the keys and I try to concentrate and the words will not come. This is exquisite agony. How many thousand times have I suffered from it. I’ve heard of writers who love to write, who are unhappy every moment they’re away from the type- writer, but I’m not one of the blessed.

I have to force myself to sit down at the typewriter and sometimes I have to leave it again after an hour or two without writing a line. Yet I’m a fast writer once I get the first paragraph down and am greatly exhilarated after writing a few pages. I have had two or three weeks go by without writing a word and during that time am tortured every waking moment. But the thoughts aren’t there and the words simply will not come.

I hear about writers who keep notebooks and plot files. I have never in the years since I started writing kept a notebook or a plot file. I have never had one plot ahead. I finish a story and start from absolute scratch on the next one. Sometimes I think I will never get another plot ... yet even- tually it comes and eventually I get started writing and the story gets finished. I have written as much as 12,000 words in a single day. My production in a year usually runs pretty close to 600,000 words. The biggest month of writing I ever had was June, 1940. I wrote “The Talking Clock,’ a mystery, during the first sixteen days of that month, then without a day’s pause swung into “Outlaw,” an historical western, and wrote that in exactly fourteen days. Two complete novels in a single month—120,000 words.

And then I couldn’t write a blessed word for five weeks.

I get my plots the hard way. I waste days “thinking,” but when everything else fails I sit down with a pencil and paper, scribble and scribble and jot down words and cross them out and finally get something that suggests an idea and worry and fret over it until it crystallizes. And then I’m off.

. . . It is now twelve o’clock and the wife has gone to bed. I find the manuscript on which I am supposed to work, but come across a copy of Erle Stanley Gardner’s new book, “The Case of the Turning Tide.” It’s a humdinger. I finish it at 2:30 and sneak upstairs to bed.

Tuesday:

This is the day I’m really go- ing to do some work. I get up at nine-thirty and dash down to the postoffice. On Tuesdays and Fridays I get the clippings from the clipping bureau. There are nineteen reviews of “The Hungry Dog,’ my latest mystery novel. Every one of them is good and I am greatly pleased.

There is a letter from Ellery Queen asking if I have any “favorite” short stories that might go into an anthology they are com- piling. (I say “they” because Ellery Queen is the pen-name of Frederic Dannay and Manfred Lee.) A letter from Bill Duchaine, with whom I worked on trade journals, back in 1927. Bill is now editor of the Escanaba, Mich., Daily Press. On the side he is press- agenting the Nahma summer school for writers and artists. In other seasons he pro- motes log-rolling and smelt runs. He does all these things merely for the good of his community; gets no pay. He was always doing something like this when I worked with him—Lord, it’s fourteen years ago. He was manager of the world’s champion log-roller, hunted jobs for friends, etc. They’ll probably give Bill a medal some day. Without Bill’s coaching I never would have been able to hold down that first trade journal job.

I have breakfast and retire to my office to work. I come across “Whistle Stop” and read a chapter in it, becoming even more annoyed than the night before. The book is all about a dirty family in a small town which goes in for incest and such. There isn’t a decent character in the book. Yet this is supposed to be a great book. If that’s LITERATURE they can keep it.

The telephone rings and it is Fanny Ells- worth. She calls me a bum and what-not. I have been doing a serial for Ranch Romances since before Christmas. A couple of weeks ago I said I would have it in this week. I now tell Fanny I am working like a dog and will have it finished next Monday.

I throw “Whistle Stop” across the room and begin searching for the Ranch Romances story. I find it, but at the same time I come across a pack of cards and for fifteen minutes I practice palming and one-handed cutting, learned from Walt Gibson, The Shadow.

I am interrupted by a telephone call from John Farrar, who asks if I have a long novelette that might go into their Third Mystery Book, which is a collection of mystery stories that they publish once a year. Of course I have many novelettes that have been published in magazines and say I will see if there is any- thing suitable.

I start looking over the magazines and work up a fine rage. When I first started to write I sold all rights to stories. In recent years I discovered that some publishers will willingly release subsidiary rights other than “first magazine,” but some won’t. I’ve even had publishers resell stories to newspapers. A couple of my best stories I can’t get a release on so have to pass them up for this Mystery Book.

Yet, I stop to think, when I first sold these stories I was glad to sell them under any conditions.

The doorbell rings and it is the special delivery man bringing me a package contain- ing the galley proofs of “The Navy Colt,” my next mystery novel (to be published in October; run, don’t walk, to your nearest bookstore). I am supposed to read these galley proofs, a chore I dislike very much. But I sit down and read about thirty sheets and first thing you know I am dozing. That won’t do, so I put the galleys aside and again tackle the Ranch Romances serial. I read what has been written so far and it doesn’t sound so bad, but I can’t start writing now, because it is lunch time. I can’t work im- mediately after lunch, so I sit down and get interested in a mystery novel, “Rattle His Bones,” by Julian Shore, a very swell job.

I read until it is time to get the mail at two o'clock. At the same time I buy the WorldTelegram and discover they have printed the interview, so I buy nine extra copies, closing out the dealer.

In the mail is a letter from a reader of the Writer’s Digest, asking me for a complete bibliography on Tom Smith, the old-time Abilene marshal. To compile such a list would only take thirty or forty hours. However, when I get home I look over my shelves of Americana and find a couple of books which contain mention of Smith. The collection of western Americana is my hobby and has cost me a pretty penny. Many of the books are quite rare.

Five o’clock comes and I am still lost in these books. At six dinner is announced and afterward I listen to the radio and continue with the frontier books. Along about nine I realize that if I am going to do any work I had better get at it, so reluctantly I put the books away. I sit down at the typewriter and spend a wretched hour trying to get into the mood to write. Around ten o'clock I finally get going and write 3,000 words without pause. It is now midnight and I read proofs on “The Navy Colt” for fifteen or twenty minutes, then get back to the typewriter. By two o'clock I have done 6,500 words. I go over what I have written and feel very sorry for myself.

Wednesday:

Since I did a good night’s work I sleep late this morning. It is almost ten o’clock when I get up and dash down to the postoffice for the mail.

There is only one fat letter, but it contains the most fascinating enclosures — royalty statements on all my books. I only get these twice a year, but if my publishers knew how eager I am for them, I’m sure they’d send them to me every week.

Royalty statements are generally sent out on May | and November 1, but they cover six-months periods, ending January 1 and July 1. I have received my statement two months earlier than I’ supposed to get them, but my curiosity had been too great and I asked for them a week ago.

There is a sheet for each book: “The French Key,” “The Laughing Fox,’ “The Talking Clock,’ “The Hungry Dog” and “Simon Lash: Private Detective.” Each contains complete details, so many copies sold up to January 1, so many between January and July. The figures are broken down, American, Canadian and foreign sales. Listed also are the second serial rights sales.

The statement for “The French Key” is especially interesting. This book was published February 1, 1940. They say a mystery novel almost always dies within three or four months, but the previous statement which I dug from the files shows that “The French Key” instead of dying by July, 1940, had sold 240 copies between then and January 1, 1940. And now the sale has picked up: 379 copies have been sold during the period between January 1, 1941, and July 1, 1941.

The statement also shows the proceeds from the advance paid by Robert Hale, Ltd., who published the book recently in England. It is broken down into pounds and shillings, which I do not understand, except that 40% is deducted as British Income Tax. When you stop to consider what England is going through it is amazing that they are able to publish and sell books and pay money to authors in the United States.

The French Key has earned me, to date, six cents a word. And the end is not yet.

I get out my clip book of reviews on The French Key and there are 174 reviews, of which six are unfavorable, all coming from one little syndicate of some guy up in Wisconsin who sells his reviews to Prairie du Sac, Deerfield, Mazomaniac. I look up the population of these three towns and find it totals less than 2,000 for all three, but I still sit there and hate this one guy’s guts. Then I wonder wouldn’t it be funnier than all hell if he was right, and all the other reviewers wrong. I think of the fantasy incident in the Ginger Rogers movie Tom, Dick and Harry, in which Ginger appears in three fantasy sequences of about five minutes each as she returns home from her date with each of her three fellows and imagines herself married to each. I decide to use this idea for something sometime, and worry it around for a half hour.

I read the rest of Rattle His Bones and make a note to review it with a four-gun rating, the highest given to the mysteries in the Chicago Daily News.

After dinner the wife and I go to the movies.

Thursday:

I read another mystery novel today, an advance copy sent me by Reynal Hitchcock, and go overboard on this one. It’s The Silver Fackass, by Charles K. Boston, a new writer, but I think it’s the best mystery novel I’ve read this year. It’s to be published early in October.

I do no writing today.

Friday:

A busy day. The morning mail contains letters from Erle Stanley Gardner, Howard Haycraft and Otto Eisenschiml, the Lincoln authority, with whom I am fighting, by mail, the Civil War in Missouri.

Howard Haycraft is the author of the recently published Murder for Pleasure, an exhaustive study of the mystery novel, past and present. Anyone who writes mysteries or contemplates doing so, or who even reads them, will benefit from reading Murder for Pleasure. I recommend it heartily.

I decide to go downtown today and de- liver the proofs of The Navy Colt to Farrar & Rinehart. In the office they show me the book jacket and I like it very much

Leaving the office of F & R, I walk up- town to Fifth Avenue and stop in at Scribner’s Book Store, where I chew the rag with Nicholas Wreden, a genuine mystery fan.

I walk across the street to the main Bren- tano store. I am talking to Bill O’Gorman, who always pushes my mysteries, when Lynne Overman, the movie star, comes in, on vacation from Hollywood, and starts look- ing over the mysteries.

Lynne is one of my favorite actors; I got to know him pretty well when I worked at Paramount Studios, three years ago, and he played the lead in Death of a Champion, one of my Black Mask stories.

Lynne Overman is quite a mystery reader and buys four books and I give him a copy of The Hungry Dog. He insists on buying a copy of Digging for Mrs. Miller, which he has read and likes extremely well, and presents it to me.

Speaking of movie actors, some of them are pretty regular guys. The first time I met Overman he was in makeup for his swell role in Union Pacific ;’ he had sprained his knee, but, not to hold up the shooting, he was going through with it, although he was in exquisite pain during most of it. You’d never know it, from the picture.

Some more reading this evening; no work.

Saturday:

This is the day I do the reviews for the Chicago Daily News so they will get them on Monday. I have read enough books, but can’t remember the exact titles, so have to search for the books in the library upstairs. The shelves have overflowed long ago and there are stacks and stacks of books piled up on the floor. Somebody has mixed them up and I have a hard time finding the ones I want to review.

I write the reviews in time for the after- noon mail and at the postoffice discover something that sets me up for the rest of the day: a check, covering an article that Esquire has bought. The check is for $150 and is in payment of a 2,000-word article I wrote one evening and had almost forgotten.

Sunday:

Sunday is always a dull day. I read and take rides in the car.

I’ve read everything I can find around the house; stall as much as I can and, at last, about eight o’clock in the evening, I get at the typewriter. At nine I stop and listen to Walter Winchell, then get back to the type- writer and knock off some 8,000 words be- fore going to bed, finishing the week with less than 15,000 words, written in two evenings. Some weeks I rip off 30,000 words. One glorious week I wrote 45,000 words but didn’t write a line for three weeks afterward.

I go to bed early because I want to lie quietly and think myself to sleep over a serious problem novel that I’ve never written.

THE INK & GRIT: MASTERS OF PULP FICTION SERIES CONTINUES HERE:

This Fiction Business By H. Bedford-Jones: A Book Review

A Million Words a Year For Ten Years Straight - Walter B. Gibson

Quantity Production - Arthur J. Burks

Max Brand: 30 Million Words of Fiction - Part I

INK & GRIT: Masters of Pulp Fiction - The Lee Child Edition

INK & GRIT: Harvey Stanbrough: A Contemporary Example of The Pulp Work Ethic

Very informative about his life and working methods.

Sold my copy of the Gruber book on ebay for a nice little score a couple years ago.