Quantity Production - Arthur J. Burks

INK & GRIT: Masters of Pulp Fiction

Don’t miss “If Morning Never Comes,” a serial adventure from

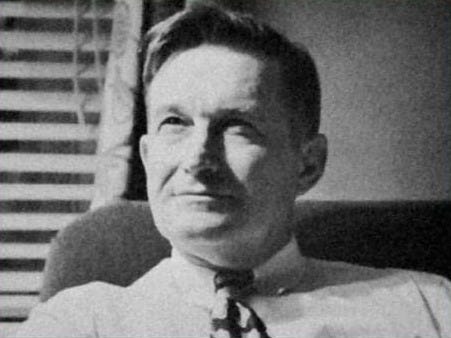

Warner and proudly published by Pulp, Pipe, & Poetry. Read the story so far and get ready for next week’s episode!The INK & GRIT series continues with U.S. Marine veteran turned fictioneer, Arthur J. Burks, who penned over hundreds of stories for the pulps, beginning his career in the 1920s when he sold a story to Weird Tales Magazine. His prolific output earned him the title “The Million-Word-a-Year Man,” along with a few of his peers.

In his article “Quantity Production”, Burks offers the reader not just a behind-the-scenes look into his process but really a love letter to the craft of fiction writing. He holds nothing back, beginning the 1937 Writer’s Digest piece with the words “This article may do you harm” - a fair warning, indeed.

“I began to write to make money. But that was not really true. I began to write because I wanted to be read, to be noticed, to have more people conscious of me, to express myself.

I have sold millions of words. I have written other millions of words that did not sell. Why, then, did I write words that did not sell - millions of them — when experience had proved to me that I could write stuff that would sell? I’ll try to sell you. It may help you through the morass of your own troubles with this writing profession. It may cause rejections to take on new meaning to you.”

On (Pulp) Speed

“A dear friend who is an agent wrote me recently: ‘If I were agenting you, I’d make you write less. I’d make you revise, and work from outlines. In other words, I’d make you slant.’

“I know myself better than fully a dozen editors, agents, and fellow writers who, down through the years, have said this to me: ‘You write too fast. You’re careless. You should take more time. You should do this, you should do that.’

“I knew myself better than various men and women who have taken my manuscript hot from the typewriter and fixed them up for the magazines. Not one of those hybrid stories ever sold, though those collaborators knew more about markets than I did.”

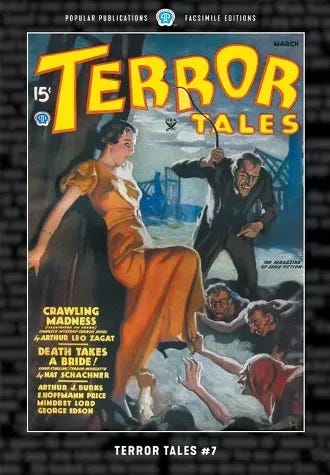

Burks, like many of his pulp contemporaries, knew that the only way to make a living in his career was to get publishable words on the page. A man ruled by deadlines and bills, Burks wrote for several paying magazines in various genres including science fiction, boxing, sea adventure, air stories, weird tales, and detective fiction among others. But what began as cut and dry attitude of writing for wages, quickly grew into a passionate love affair with storytelling.

On Love of Writing

“When I am not writing, or thinking about a story, there is no living with me. I pace the floor. My family gets out of my way or gets stepped on. My children get kicked across the room. My wife gets her head bitten off if she smiles and says: ‘How are you, darling’?

Traffic outside my window drives me nuts. Everything is wrong, nothing goes right. I hear every sound and it rasps my nerves like a rusty file drawn over a rusty rasp. I hate my food and my drink. I hate everybody including myself. I won’t do anything anybody wants me to do. I can’t stay inside, I won’t go out. I’m utterly and completely impossible, and the fact that this is so makes me worse than ever.

But when I’m writing, ah, there’s the difference! I like to write, I have to write or go mad. And the more I want to write the faster words tumble over themselves to get onto paper. I’m happy. I’m as interested in the outcome of my story as I dimly hope my readers will be—though right then I don’t think about readers or editors or anybody else, except the matter of getting my story on paper.

My fingers are simply not fast enough, because two of mine do the work of ten. I go so fast, am so burned up with my story, that my brain goes right on while I’m changing the paper in the machine…

And when I’ve finished the story it may or may not sell; but by the Lord Harry that story is mine! I gave birth to it. I was happy to do it. I wanted to write it. I enjoyed every second spent at the machine. And I’m still happy about it.”

On Rejection

“It sells or it doesn’t sell. Quite often it doesn’t. And even if I do need a check, there are other stories in the mail, and experience has taught me that a certain percentage of them will come romping home with the dough on their tails. And the reject is money in the bank! How do I explain that? I’ve sold stories that were seven years old. I’ve sold stories that were over two years old. I get more rejects than any so-called 'successful’ writer in the pulp field. I think I appear in about as many magazines as the general run. Percentage takes care of me.”

Burks continues with a fervent address on how he detests writing “with a slant” (writing for acceptance at a particular market):

On Slanting

“I’m a good enough hack to make a salable story out of that returned outline, just as I’m a good enough hack to make sweeping revisions if I have to get paid to meet a bill. But the fire is gone. Writing has become a chore instead of a delight….Yes, I get the money for it, but there’s no great joy in that either…The story is a child born on the wrong side of town.

“But if slanting disgusts me, makes me utterly and completely unhappy, to the point where I can’t write at all, what good is money? I’ve made a lot of it in my time, so much that I learned something that every writer knows, or will know sooner or later—that money is far from being the whole fruit.

“Even pulpsters—who sneer at ‘art’ — need food for their souls on occasion. Else how can they enjoy life?”

A workman writer with the heart of a romantic, Burks did what he had to do to make his living during the economic difficulties of the Great Depression. However, the desire to write and the commitment to telling interesting and entraining stories seems to have taken the center of his life. His love of telling stories, his ultimate reason for returning to the typewriter, to his work, was greater than the sum total of any paycheck he’d earn. That love kept him going.

Or to put it in his own words:

Take it from me. You’ll last longer in the profession that makes you happy. The slanter is more “successful” than I am; but I’m curious about where each of us will be ten years from now if we live.”

Arthur J. Burks

(1898 - 1974)

Till next time.

Insightful and fascinating.

Fantastic piece!