Editor’s Note:

Welcome, dear reader! Today we are lucky to have a new short story from Brady Putzke. I’ve had the pleasure of reading Brady’s fiction for a few years now, including his horror novel, Dream House, and always look forward to a new story from him. He is quickly on his way to becoming a master storyteller.

For your reading pleasure, The Archivist.

- Frank Theodat

I am the Archivist. I live among the stacks. Discs, codices, leather volumes, papyri, paintings, drawings, sculptures, artifacts of every shape and kind. I am the keeper of my people’s history. I watch over the inheritance that makes us who we are, even if no one cares any longer.

I have never had time for love, nor inclination to seek it, save for love of my people. My romance has been with relics, the thoughts and aspirations and dreamings of my people made manifest in precious things. I am a protector. I am an ark. I carefully do my sacred duty to carry the glory of our ancestors safely above the deluge of indifference that floods the streets below. I watch the people come and go from my tower. They think there is bliss in their ignorance, as the old proverb says, but they give no thought to blush at the embarrassment of riches housed in the Great Archive as they pass by daily, speeding away on the powered walkways to their pointless work and play. Still, there is some feeling I find in me. Perhaps it is envy. I see a young man hand in hand with a young girl, both full of an exuberance they do not comprehend, and I feel a wanting. Yet, I content myself with my noble calling.

I think often of that place they called Alexandria. My home and charge is not threatened with fire, but the carelessness of my people, whom I love and envy and despise for their benightedness, terrorizes the heavenly place in which I live and work just the same.

I am not a brilliant man, I think. Certainly not like the towering geniuses that birthed the precious things I keep. I am not Shakespeare, nor Hafiz, nor Homer, nor Shikibu, nor Tolstoy, nor Cezanne, nor Rodin, nor Mozart. I am not the one called Christ, nor the one called Prophet, nor the one called Tathagata. Nor am I the ones who came after the Migration. Jinhai, Agarwal, Smith, Gudmundsson, Lady Bezaroth, Solovyova, Abadi. I have learned these long years to know their languages, their places and customs, to understand. But I lack whatever was in them to create. Still, all people have their role.

Go now, you fretful man. There is cataloging to be done.

I had not had a visitor to the Great Archive for many years, so many that I could not count them, when she came. I am to all who see me, to the few who do see me, a man of thirty-five years. Yet it has been hundreds more and I keep no count. Somewhere is a record.

She was perhaps of twenty-three real years, unaffected by the intrusion of technology.

The Archivist is kept young by a strange magic they call “science”, lacking so in wonder at the miraculous as they are. An enzymatic therapy was discovered to preserve and elongate human telomeres and keep certain persons young and alive indefinitely. I take solace in the fact that the Consortium deemed me of enough importance to keep me in the therapy, enabling me to carry out my hallowed commission for centuries. The contract stipulated only that I could not leave my post.

I contented myself with my noble calling.

Visitors were welcome on the upper levels, as in the days when people still attended museums. When she came to see me, or rather the Archive, for the first time, she wore a yellow sundress and brown suede sandals. I knew from the collection of artworks and sartorial histories that these were not items of clothing currently in fashion and had not been for a long time. I also knew that she was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen. And this thought from a man whose very life is the cataloging and maintenance of beauty.

“Hello. I’d like to see the Monets, please,” she said, after having paged me to the foyer from an upper level. She held a wicker basket behind her and bobbed to her tiptoes and back. Her whole aesthetic presence was derived from the latter half of the 20th Century, Standard Earth, from North America. I had a fondness for such things, but she could not have known this. Perhaps the great books were right about the mingling of love and destiny. Not love, of course, but infatuation. All things I had read of.

“Oh, yes. Of course. This way, Miss.” I swept my arm widely with an open hand, welcoming her to the first ground level.

“Lucy. I’m Lucy Hawthorne,” she said. The name was even of the same time and place. My curiosity got the better of my manners.

“I beg your pardon, Miss, but you seem to be somewhat of an anachronism. Is that rude? I find you a puzzle.”

“I just like old things,” she said. “Don’t you? They’re quite fine.”

“I do. It is my life to be among the relics. Preserving and cataloging. Your name as well, though, is old. Did you inherit this fascination from your parents?”

“I suppose I did. I don’t think much of my name now. But, in my school days it was considered odd, you’re right.”

My heart sank then, for I feared we had already run the course of things to discuss. Ah, the Monet pieces! Of course. I wanted very much to impress her. I gave a beckoning wave for her to follow me to the paintings.

“What’s your name?” she asked.

“I am the Archivist.”

“That’s a job, silly. What about your name?”

I stopped walking abruptly. I felt my jaw clench almost against my will.

“It is a sacrosanct duty, Miss. Not a job.”

She smiled with an impossible radiance. The tension faded.

“I apologize if that was rude again,” I said. “I do not get many visitors here. Perhaps only reading of etiquette is not enough.”

“You’re funny,” she said.

I laughed. God, I could not remember the last time I had laughed. The Archive collected my people’s greatest humorists, of course. But I never read them. She liked me, I supposed. My study of the great psychologists and philosophers had not prepared me for the burning and twisting feelings in my chest. I was almost dizzy with anticipation. My face grew warm.

We walked the long, painting-lined halls to the room that housed the Impressionists. She entered first, giddy, and held out a hand to me. I took it eagerly. Her hands were soft and fragile and unlike anything I had ever felt before. She led me to the tiled section of the room encircled by the largest Water Lilies, some longer than 600 centimeters. At 200 centimeters high, they enclosed us as if we occupied a beautiful park. Yet filtered through the mind’s eye of the artist, it was as much a mystical dreamscape as it was anything so mundane as a park.

She took a red and white checkered blanket from her basket and spread it on the floor.

“I’ve brought a picnic,” she said.

“That is very unusual of you, Ms. Hawthorne,” I replied.

Her eyes became downcast.

“Again I have been uncouth,” I said. “I am sorry. It is a lovely gesture.”

Light returned to her eyes as she unpacked red grapes, white wine, brown bread, and yellow cheeses. There were aged salamis too and almonds and olives. She made a small plate for me. The bouquet of tastes was an extravagance compared with the machine-prepared meals I received in my upstairs quarters. As with the feelings Lucy inspired, reading of things like the foods we were now enjoying did no justice to the experience. I was in heaven, as the old saying says.

“They are beautiful. More so than I imagined,” she said, eyeing the paintings with unveiled awe.

“Yes, Ms. Hawthorne, they are beautiful.”

“Please, call me Lucy.”

“Very well, Lucy. Yes. I learn more of beauty every day,” I said.

I was struck with a sudden fear that she knew I was speaking of her, my suspicion spurred on by the blush that rose in her pale cheeks. Still, she smiled. She liked me, I supposed.

We sat in reverence, eating, speaking sometimes of art and books and the lack of taste for either in the workaday world outside. She spoke of Utilitarianism and the plague it wrought, though scarcely any knew the philosophy’s name today. She was terribly bright and achingly beautiful. I had the thought that I loved her. Too soon, of course. But perhaps not. Stranger things were told of.

She glanced at a small old-fashioned (as everything was with her) gold timepiece which she wore on her delicate left wrist.

“Oh dear, I must be going. Thank you very much, Mr. —” She broke off, again searching for a name to call me.

“I am the Archivist, Lucy. I know it is strange to you, but it’s the only name I’ve ever known.”

She giggled innocently.

“Can I call you Archie?” she asked.

“I suppose that will be fine,” I said, trying to hide my excitement at her special attention toward me.

“Okay, Archie. I’ll see you tomorrow,” she said.

“I beg your pardon?”

“I simply have to see the Botticellis next. Is that alright?”

“Oh yes, that will be most good.”

She grinned and kissed my cheek and darted off, leaving her basket and all the picnic goods. She stopped in the doorway and waved. I supposed she would retrieve her belongings tomorrow. I also supposed I was in love.

She came every day for two weeks after that first picnic among the Monets. We toured the Botticellis, as she requested. We sat in the augmented reality theater that displayed the bold interactive works of Jinhai. We listened a whole day to bebop jazz in the audio stacks, feasting on more delightful foods, laughing and talking of beautiful things. We wondered at the strange surreality of Dali. We sat before the statues of Greece, thoughts in my head of perfect bodies and the things they could do, and I hoped she had the same thoughts.

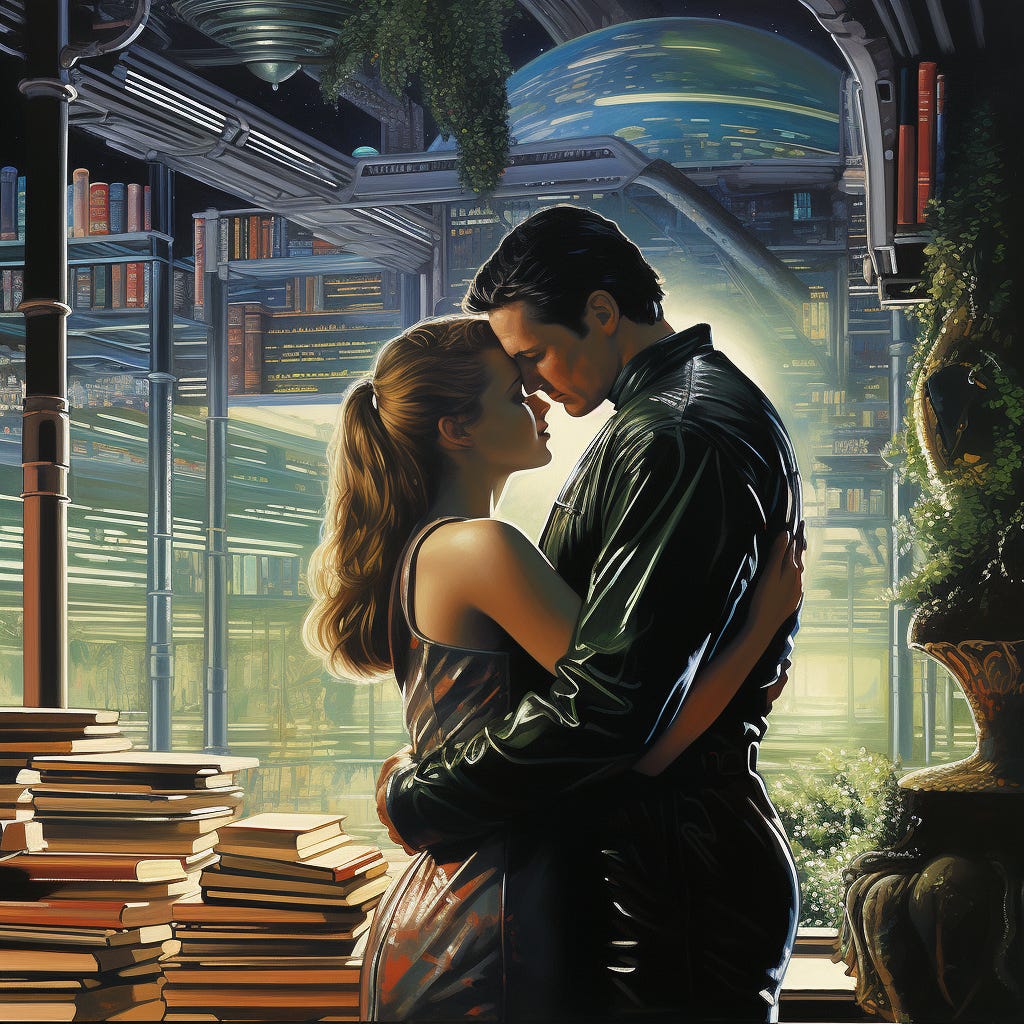

We kissed. I held her. I dared not ask for more and we refrained from retiring to my quarters, though I felt she might have desired it. She would not be so bold as to say.

I passed two weeks with her in a euphoria the beauty of which was unmatched by anything in the Great Archive.

She came again the third week, looking radiant as always. She kissed me as a greeting. My heart leapt. We set off for another picnic among old astronomical devices and ornate maps from Earth’s past.

“These lovely pieces tread the line between art and technology,” I said.

“Yes. They truly do, Archie.”

We sat a moment with our thoughts. Mine were of her.

“Doesn’t the Great Archive house later, more advanced technological records?” she asked.

“Yes, it does. In the basement levels. Though they are not open to the public.”

“But you can see them? I bet there are wonderful things down there.”

“I do not find them so appealing as the works of art up here, but I am tasked with their keeping as well.”

“Can I see them?” she asked.

“No, Lucy, I am afraid they are sealed for fear of falling into hostile hands. I alone know the door codes, elaborate mathematical sequences I was trained from my boyhood to remember.”

“Oh, well, that’s okay,” she said. “There is plenty to enjoy up here.”

She pulled my robe and my lips met hers. I learned more of beauty every day. And of love.

She did not come the next day, but the fires did.

Windows shattered from the explosion of missiles. The dreams of my people burst into cruel and relentless flames. The water systems of the Archive were no match for the horrible barrage of disfiguring destruction.

I had failed in my duty. I had failed to protect the beauty I loved. I worried for Lucy. War was underway and I knew not where she was. Nor could I leave my post.

I sat and I wept.

The captain must go down with his ship, as the old proverb says.

A voice came over the Great Archive’s central sound system.

“This is Commander Grales of the Outworld Allied Forces. We have one Lucy Hawthorne in our custody. The Archivist will board our craft from the rooftop. Compliance will secure the release of the girl and halt the destruction of your Archive.”

I raced with every ounce of speed I could muster to the elevator. My lungs burned with smoke and exhaustion as I pressed the button for the rooftop.

It was raining when I stepped onto the landing area. I felt the cool relief that came from water born of the sky. I had read of such things. I was not to be outside, but I had a higher duty now. To a higher love. My dear Lucy.

Two brutes grabbed me by the underarms, surely bruising my ribs, and carried me to the assault ship. I was shoved inside and tumbled across the floor, my face coming inches away from black leather jackboots. I smelled sulfur that was wafting from the windows below. I looked up to see the face of a fair young woman in OAF regalia. A general perhaps. Her hair was pulled back into a tight bun, her features harsh and cold, her lips thin with contempt.

God! It was my Dear Lucy.

“Now, let’s see about those codes,” she said, holding a stiletto knife to my temple.

I answered her with a small piece of my people’s dreams that I had by heart:

“I hold it true, whate’er befall,

I feel it, when I sorrow most;

‘Tis better to have loved and lost

Than never to have loved at all.”

Excellent. And stabby. But excellent.

I suspected that the whole thing was too good to be true, lol.